寨卡疫苗研发至少还需要12年?

最近,美国出现寨卡病毒,但这种主要由伊蚊传播的病毒已在非洲、东南亚、太平洋半岛、南美洲、中美洲等地区暴发。CDC警告,已经怀孕的妇女和准备怀孕的妇女近期都不宜前往这些地区。

与其他几种传染病不同,目前还没有预防寨卡病毒的疫苗和治疗寨卡病毒的药物和方法。得克萨斯大学医学院的一支专家小组目前专门从事研究寨卡病毒的工作,他们的主要任务是研制预防寨卡病毒的疫苗。进行此项疫苗研制的专家表示,寨卡病毒疫苗可能在2年后进入试验阶段,但最终通过检验、投入临床使用可能还需要10年时间。

去年年底,巴西、菲律宾和墨西哥批准了全球首个登革热疫苗。然后,结合本文中登革热抗体对寨卡病毒的免疫反应,我们有理由相信,寨卡疫苗的研发能够加速。

接触登革热病毒可能提高寨卡病毒感染力

资料来源:英国伦敦帝国学院

伦敦帝国学院相关研究声称:既往接触过登革热病毒者可能会增加寨卡病毒感染的可能。早期的实验室研究结果已发表在《自然》免疫学专栏上,表明近期寨卡病毒的暴发,可能与在某种程度上可能是由之前接触过登革热病毒驱动的。

法国巴黎巴斯德研究所和曼谷玛希隆大学的科学家联合研究认为:寨卡病毒对人体自身防御系统而言,就像“特洛伊木马”,允许其进入未被发现的人体细胞。一旦进入细胞内部,它便迅速复制繁殖。

加文的资深学者、帝国医学院院长Screaton教授的相关研究表明:“虽然这项工作处于研究的早期阶段,但他表明以往接触过登革热病毒者可提高寨卡病毒感染力。这可能是目前寨卡病毒为何一直在登革热流行地区发生严重暴发的原因。我们现在需要进一步的研究来证实这些发现,并推动疫苗研发的进展。”

该小组发表在《自然》杂志上的第二项研究建议:针对登革热病毒的致病机理,可研发出一个潜在的目标抗体,可能也可以结合寨卡病毒,并将其杀灭。

最近几十年,感染登革热的人数急剧上升,该病毒每年可引起3.9亿人感染,且40%的世界人口居住在疫区。

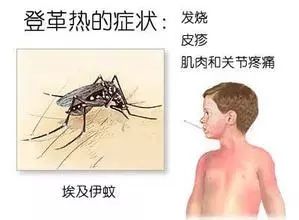

登革热病毒结构类似于寨卡病毒,它们同属于黄病毒科,且两者均由伊蚊传播。

在威康信托基金会和医学研究理事会的支持下,研究人员从已感染登革热病人的体内分离出登革热病毒抗体。在国家卫生研究院帝国生物医学研究中心的支持下,将其与Zika病毒一起注入至人类细胞培养物中进行培养。该项研究发表于新一期《自然》杂志的免疫学专栏上。

他们的研究结果表明:由于病毒之间的相似性,登革热抗体可以识别并结合寨卡病毒。重要的是,现有的登革热抗体可以通过一个被称为抗体依赖性增强(ADE)的效应来增强Zika病毒的感染力。

以往感染过登革热病毒的患者,第二次感染登革热时常常比第一次的感染表现的更为严重。

当人体首次感染登革病毒之后,自身免疫系统针对该病毒产生特异性抗体。抗体是免疫系统产生的大分子蛋白质,附着并破坏侵入机体的细菌或病毒。当人体再次受到相同的病毒入侵时,抗体早已对同样的入侵者做好攻击的准备。

然而,登革热病毒有四种不同的血清型。如果人体二次感染不同类型的登革热病毒时,仅有首次感染后产生的部分抗体可与该病毒结合,并且无法预防感染。

抗体与病毒松散地附着,然后被免疫细胞吞噬。随后,这种免疫细胞通常会直接杀伤病毒。但由于病毒没有被正确地附着,病毒一旦进入人体,便被免疫细胞破坏。若病毒逃逸免疫监视,便可复制出更多病毒,从而提高了感染的几率。

这项新的研究表明,曾接触过登革热的人遇到寨卡病毒时,会表现出现同样的症候。由于病毒之间抗原表位的相似性,存在于体内的登革热抗体可与寨卡病毒结合。然而,抗体与寨卡病毒的结合并不安全,因为登革热抗体只是便于寨卡病毒进入人体并复制的免疫细胞。

这两篇论文来源于:威康信托基金会,医学研究理事会,国家卫生研究院生物医学帝国研究中心和欧盟第七框架计划。

英文原版

Dengue Virus Exposure May

Amplify Zika Infection

Previous exposure to the dengue virus may increase the potency of Zika infection, according to research from Imperial College London. The early-stage laboratory findings, published in the journal Nature Immunology, suggests the recent explosive outbreak of Zika may have been driven in part by previous exposure to the dengue virus.

The study, which included scientists from Institut Pasteur in Paris and Mahidol University in Bangkok, suggests the Zika virus uses the body's own defences as a 'Trojan horse', allowing it to enter a human cell undetected. Once inside the cell, it replicates rapidly.

Professor Gavin Screaton, senior author of the research and dean of the Faculty of Medicine at Imperial, said, "Although this work is at a very early stage, it suggests previous exposure to dengue virus may enhance Zika infection. This may be why the current outbreak has been so severe, and why it has been in areas where dengue is prevalent. We now need further studies to confirm these findings, and to progress towards a vaccine."

A second study by the same team, published in Nature, suggests an antibody that works against the dengue virus may also neutralize Zika, providing a potential target for a vaccine.

Dengue fever has risen dramatically over recent decades and the virus is thought to cause around 390 million infections each year - with 40 per cent of the world's population living in areas of risk.

The dengue virus is similar to the Zika virus; they belong to the same viral family, called the Flaviviridae, and both are transmitted by the Aedes mosquito.

In the new Nature Immunology paper, supported by the Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council, the researchers used antibodies that recognise the dengue virus collected from individuals who had been infected with dengue. The team, who were also supported by the National Institute for Health Research Imperial Biomedical Research Centre, added them to human cell cultures, together with the Zika virus.

Their results suggest dengue antibodies can recognize and bind to Zika, due to the similarities between the viruses. Crucially, they also suggest that pre-existing dengue antibodies can amplify a Zika infection through a phenomenon called antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE).

This has been previously identified in dengue fever, and is thought to be why a second infection with dengue is often more serious than the first.

When dengue first infects the body, the immune system makes antibodies against the virus. Antibodies are large proteins that latch onto invading bacteria or viruses, neutralizing them and enabling the immune system to destroy the pathogens. The antibodies are then primed to recognize the same invaders should another attack occur.

However, there are four different types of dengue virus. If someone is infected a second time by a different strain, the antibodies from the first attack can only partially bind to the virus, and are unable to prevent infection.

The antibody, with the virus loosely attached, then shuttles into an immune cell. This immune cell would normally then kill the virus, but because the virus is not properly attached, it breaks free once it gains entry to the human immune cell. Here it hijacks the immune cell's machinery to replicate more viral particles, enhancing the infection.

The new study suggests the same phenomenon occurs when a person who has previously been exposed to dengue encounters Zika. The existing dengue antibodies latch onto Zika, due to similarity between the viruses. However the antibodies are unable to latch onto Zika securely, and so the antibody simply facilitates entry of Zika into the human immune cells, where it replicates.

The work in both papers was supported by The Wellcome Trust, the Medical Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research Imperial Biomedical Research Centre and the European Commission Seventh Framework Program.

Source: Imperial College London